19th Century Latin American Heroes

Sherlock Holmes, Professor Abraham Van Helsing, Wyatt Earp, Nikola Tesla. These are some of the many 19th century historical and fictional heroes that inspire us in the steampunk community. We create our steampunk personas to be adventurers, inventors, and challengers of the unknown, based on the fictional stories or real life events that took place in that century. But most of those stories tend to be centered around characters of historical figures from the Mighty British Empire or the new frontiers of the United States of America of the 19th century. Of course, the reality is that steampunk, as a subculture, tends to be eurocentric due to its original basis. But steampunk can expand on its original concepts. There was more to the world in the 19th century than the British Empire and the American Wild West. For example, many amazing stories and characters can be found in Latin America. The 19th century was a time when many Spanish colonies were fighting for their independence and many heroes real, and fictional, were forged. The following are the stories of some of them.

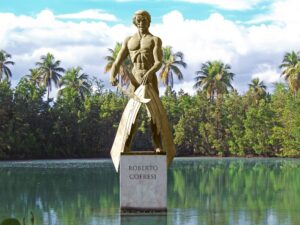

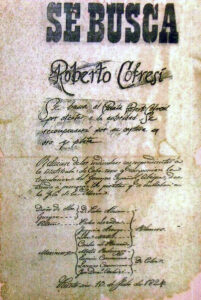

Roberto Cofresí y Ramírez de Arellano “Pirate Cofresí”

The last of the great pirates of the Caribbean. A man with a history shrouded in legend, it is said that his family was a wealthy noble family from Austria that fell out of favor after his father Francesco Kupferschein killed a man in a duel in 1778. His family fled to Barcelona,Spain, and then settled in the town of Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. Roberto Cofresí was born on June 17, 1791, the coastal city of Cabo Rojo was his native town. The ocean became his best friend. Since childhood, he dreamed of becoming a great sailor, realizing his dream when he was a teenager by purchasing a small boat he named El Mosquito.

In the early 19th century, Puerto Rico was going through hard economic times. The Spanish Empire was in decline and the corrupt local government demanded heavy taxes. Even though his family was of noble birth, they also felt the sting of the oppressive government and their household fell into poverty. Cofresi then decided to become a pirate to fight the suffering and squalor that tormented the poor people of the island. Cofresí’s success was an oddity, nearly a century after the end of the Golden Age of Piracy. For seven years, the daring and courageous pirate attacked European and American ships, robbing them of their precious cargo that he generously shared with the poor people of the island. But eventually, his luck came to an end. In 1825, a multinational effort to capture him finally ended his adventure. He was executed in San Juan, Puerto Rico on March 29, 1825. He was only 26 years old. Different versions of his legend have been told. For many, he was the Puerto Rican version of Robin Hood, a courageous rogue that broke the law to help his people. It is said that his treasure is buried somewhere around the beaches of the coast of Cabo Rojo, still waiting to be found.

José de San Martín

Hero of South American independence, liberator of Chile and Peru. He was an Argentine general and governor who led his nation during the wars of Independence from Spain. His military campaigns changed the history of South America during the decolonization process that occurred in the early nineteenth century. Its strategic lucidity is due to the military approaches that would lead to the independence of Chile and Peru, the nerve center of Spanish power whose fall would lead to that of the entire continent. Born in 1778, he joined the Spanish Army at a young age and in 1808 he fought against the Napoleonic army that invaded Spain. His bravery against the French invaders at the Battle of Bailén would earn him the rank of cavalry lieutenant colonel. After this brilliant career in the Spanish army, and shortly after the outbreak of the emancipatory revolution in America, San Martín, who had maintained contacts with the Masonic lodges that were sympathetic to the independence movement, reoriented his life towards the emancipatory cause. The feeling of his American identity and his liberal ideology, developed in the spiritual climate that emerged after the French Revolution and in reading the French and Spanish encyclopedists and enlightened artists, determined him to contribute to the freedom of his homeland.

His leadership grew rapidly, first in command of the Regiment of Grenadiers and later in the leadership of the Army of the North. Then, in 1817, San Martín would complete one of the most extraordinary feats: the Crossing of the Andes. The crossing was arduous, as flatland soldiers and Gauchos struggled with the freezing cold and high altitudes, but San Martín’s meticulous planning paid off. In 1818 he defeated the Spanish army and achieved the independence of Chile, and later 1821, he liberated Peru. San Martín was named “Protector of Peru” and began setting up a government. His brief rule was enlightened and marked by stabilizing the economy, freeing slaves, giving freedom to the Peruvian Indians, and abolishing such hateful institutions as censorship and the Inquisition. Years later, San Martín returned to Argentina, but discouraged by the internal struggles between different government factions, he left again for Europe. He passed away on August 17, 1850 in France. “I wish my heart were deposited in that of Buenos Aires”, was the posthumous will of the military man. Since 1880 his remains rest in the Chapel of Our Lady of Peace, located in the Metropolitan Cathedral, permanently guarded by two grenadiers.

Luisa Capetillo

Luisa Capetillo was a Puerto Rican anarchist, a pioneer of feminism, and trade unionist. She distinguished herself as an intellectual, writer, journalist and labor leader. She resisted social conventions and drew attention to her ideological positions in multiple ways. Luisa Capetillo was born in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, on October 28, 1879. Her parents were Luis Capetillo, of Spanish origin, and Margarita Perón, of French origin. Luisa had access to French literature as she learned that language from her mother and her eagerness for reading made her self-taught. She worked as a reader in tobacco factories in her hometown where she joined the Tobacco Twister Federation, an affiliated union to the Free Federation of Workers of Puerto Rico. She traveled throughout the island organizing tobacco and cane workers in the fight for better working conditions. She favored free love, rationalist schooling, spiritualism, and vegetarianism and exercise as a lifestyle. She had five children without being married, and In 1919 she was the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear pants. It was so scandalous that her affront to the social norms of the time made headlines in the local newspapers.

She lived in the United States (New York and Tampa), Cuba and the Dominican Republic. The history of her life was rediscovered during the seventies of the twentieth century, becoming recognized in Puerto Rico as an icon of the country’s struggles. Luisa distinguished herself for being an active woman and for her struggle for women’s equality and workers’ rights. Luisa Capetillo promoted anarchist ideals and feminism through her writings. Free love is a recurring theme in its texts, as are equal rights for women, salary improvements for workers and class struggle in favor of libertarian socialism. Everything she did was based on her words: “I am socialist because I aspire that all the advances, discoveries and inventions established belong to everyone. That their socialization be established without any privileges. A Woman must change her situation at any cost.”

Besides real life heroes, we can find inspiration for our steampunk creative endeavours in Hispanic 19th century heroes such as the following:

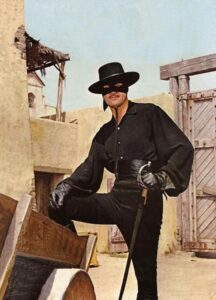

El Zorro

Perhaps the best known, El Zorro was the creation of Johnston McCulley, in 1919, in his novel The Curse of Capistrano, where Don Diego de la Vega becomes Zorro in the pueblo of Los Angeles in order to help the downtrodden and helpless and to right wrongs inflicted on the poor. His identity is not known because Don Diego wears a black mask. He leaves behind him the mark of his identity, a Z which he carves on people with three swift strokes of his rapier. The setting is in California, before the independence of Mexico from Spain. Most of the villains are Mexican and Spanish, full of greed and corruption. Don Diego woos señorita Lolita Pulido who cares not for him, but is secretly in love with the dashing Zorro, who happens to be Don Diego. Well, you know how it goes. Several sequels made the character popular which prompted the making of several films. The Mark of Zorro, with Douglas Fairbanks, was released in 1920 to great success, which encouraged McCulley to write many more Zorro novels. Many movies have been made since the first, the latest being The Legend of Zorro, 2005, with Antonio Banderas. Zorro helped make Spanish things popular in the United States, especially with women who saw, and still see Zorro, with his mask, moustache, sombrero cordobés and cloak, a dashing and romantic figure.

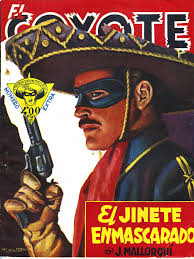

El Coyote

El Coyote was created by José Mallorquí Figuerola (1913-1972) who was a pulp and feuilleton writer from Barcelona, Spain, and made a living translating novels from the French and English languages. He was very prolific and penned western-like cheap novels until he hit on El Coyote, a copy of Zorro, and went on to write over 190 novels based on this fictional character. Novels, films and comic books were read by millions of readers. El Coyote is in reality Don César de Echagüe, a rich California hacendado who returns to his Hispanic land in 1851, to find it invaded and conquered by ruthless Yankees set on getting hold of the gold mines owned by the Hispanic inhabitants of the newly incorporated territory. Don César leads a double life: as a cowardly hidalgo and as an intrepid and fearless champion of the rights of the Hispanos, in the guise of El Coyote, with mask and cloak, and Leonor de Acevedo for a girlfriend. The tyranny of General Clarke in California and the reign of terror and plunder to which he subjects the native California population is checked by the hero of our novels, El Coyote.

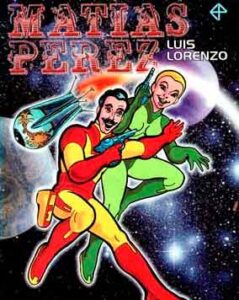

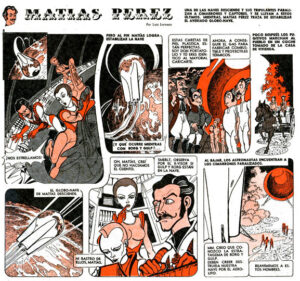

Matías Pérez

Perhaps my personal favorite, this character was actually based on a real life 19th century adventurer that met a tragic end, but who’s adventures continued as a comic book character. Matías Pérez was a 19th century Portuguese awning-maker, residing in Havana. On June 28, 1856, during his second ascension in his hot-air balloon, Ville de Paris, he was swept away by the wind and vanished without a trace. When referring to something that has disappeared, Cubans still say ‘it flew away like Matías Pérez’.

In 1969, the imagination and the pen of local artist Luis Lorenzo Sosa converted the vanished awning-maker into a space hero: after an encounter of the third kind, astronauts from the superior planet Strakon who were exploring Earth were impressed by his bravery and courage and recruited him for their cosmic crew. The science fiction adventures of Matias Pérez have appeared in several series, both in the children’s weekly Pionero as well as in books from the editorial Abril, and they were very popular. Every child and adolescent were familiar with his anachronistic moustache, with its crooked, stiff edges and his keenness for the tamarind juice, his girlfriend Blina and his friend Smerlt, Strakonians with weird hairdos, and his funny but ingenious creole collaborator Leocadio. But they also knew his enemies: the fearful conqueror Kuantrespit and his bungling cohorts, the immoral bandits Borg and Gulp and the cruel batrachian tyrant from the planet Kerlum, Sap-O-Tor.